1. People in Turkey are very becoming towards western foreigners.

2. They keep to themselves and convey a sense of safety and cleanliness.

I was eager to know how this would hold in my own experience.

Turks are no Europeans either: even though Turkey spans, to the north of Marmara Sea, what is conventionally defined as Europe, their contact with European cultures has been superficial compared to, say, the Hungarians. And the Hellenistic/Bizantine background remaining from pre-Seljuk times is confined to the wealth of monuments from those times.

The connection goes to the point that it is quite common, in the genetical Babel of Anatolia, to find people with a vague Mongolian appearance, in the eyes, in the cranial shape, in the skin colour and/or in the hair. There is no doubt to me that in Turkey one is visiting a version of Central Asia that happens to lie in the extreme West, as much as Morocco is the "Far-West" to Arabic culture. Both really nice, yet each in its own manner.

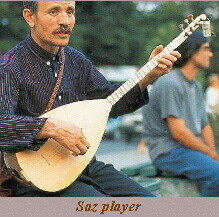

Concerning the music, again one finds a lot of arabic influence both

in styles of singing and in instrumentation. But the saz, a 3 or 4-stringed kind

of luth with thin arm and strongly metallic sounds that accompanies the

voice in all its nuances, is a very Turkish instrument. From what I know,

its music was kept through troubadours (as;ik) in the provinces

to the present day, and has many genres, probably in connection with different

traditional dances. Though it is another characteristic craft, the much-coveted

art of the kilim appears to be Anatolian heritage, not specifically

Turkish.

singing and in instrumentation. But the saz, a 3 or 4-stringed kind

of luth with thin arm and strongly metallic sounds that accompanies the

voice in all its nuances, is a very Turkish instrument. From what I know,

its music was kept through troubadours (as;ik) in the provinces

to the present day, and has many genres, probably in connection with different

traditional dances. Though it is another characteristic craft, the much-coveted

art of the kilim appears to be Anatolian heritage, not specifically

Turkish.

Furthermore, the Turks are very quiet. Very seldom did I see them thundering their voices, whatever the situations they were in. Yet, they look merry, chatting, smiling and laughing very easily -- only quietly. Indeed, they will throw reproaching looks at you if your voice is raised too high (and it does not have to be very loud) for too long (which is relatively short). As a "loud" Latin, I took a lesson from this; such behaviour helps a lot in conveying that gentle touch of theirs -- and it also reminded me of the conduct seen in some nations from the Far East.

But I got the feeling that, if for some reason Turks get angry, there are no shortcomings in their way to deal with the cause of their anger...

Finally, a Turk will help you free of charge. Not only because they want foreigners to be happy while in Turkey, which is quite common to many countries: it is their incredible readiness to go out of their way to do something for you. I witnessed this many times (see below).

The remainder are more diversified in approach. The toughest ones are the more provincial people, very conservative, not used to foreigners whom they shun. But if with some pretext they had to communicate with me, like asking what time it was for example, they became more tender quite easily. On the other extreme, those living in major towns like Istanbul, and, perhaps even more, in Izmir, were immediatly friendly. First, it was easier to find someone who managed to speak a little English, or sometimes German, and that helped a lot in evoking a friendly attitude; but even in case they didn't, the mere fact that I tried to speak a few words in Turkish seemed to impress them, though they did not remind that it would be better to reply sl-ow-ly (they speak too fast!!)... But all this might not apply if the foreigner speaks Turkish fluently.

Anyway, in general the people you meet in the streets, transportation, etc., are very accessible. And how they are curious! One of the things the Turks always want to know is where do you come from, then what is your work, etc.. If they get a little more familiar, they will go on to ask if you are married, how many children do you have, and so on... they will ask such questions so directly that it will appear blunt, or even a bit intrusive. Sometimes I was tired of answering the same questions again, especially when dodging employees trying to catch me to their restaurants, or at the Covered (Grand) Bazaar in Istanbul. But to the occasional encounter in a café or in the street, I got used to this curiosity and even felt that as amusing. No, the travel operators will not ask you those questions.

In the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (KKTC) it is said that there are two kinds of Turks: those who were raised there, and those immigrated from Turkey. There were two ways of telling them apart: one, is that only the mainland Turks will ask those habitual questions; the other, is that some of the Cypriot Turks, if old enough, speak very good English, something that isn't almost found in Turkey if one does not count in the travel operators. But, in spite of the opinion on the Greek part of the island, the main cultural traits expounded above appear to be identical between those two "kinds".

2. Even though the Turks can be said to be very honest, sometimes in restaurants (especially in Istanbul) the visitor can be confronted with inflated bills. Once we were asked to pay about the double of what we should for a meal, and we did not protest then because we were embarassed and freshly arrived, hence unaware; a few days later, another bill had an extra item of 1 MTL (some 2.23 US Dollar by Summer 1999), and this time we demanded, even if they could not speak anything but Turkish, that this was corrected. It is also common that such people "forget" to bring you the change. Anyway, never fall into the trap of asking wine for the meal. First, it is not the Turkish way at the table; second, with the exception of KKTC, their wines aren't that special (most are for export to Germany); third, 6 MTL for a bottle is not easy to swallow!

3. Turks from other parts of the country also warn that in Istanbul one should watch the wallet, like in trams or buses. Fortunately, nothing happened, but I was indeed trying to be careful, there and elsewhere. Never ever did I feel unsafe during my stay in Turkey.

4. In KKTC haggling won't do. And in Turkey you should try that only when buying expensive stuff in the Covered Bazaar or specialty shops, otherwise it is not worthy. Modern shops in Istanbul use fixed price, sometimes they display that, even the sales (indirim) are fixed. In the regular bazaars haggling might work, but the products do not seem to be worth the trouble.

5. As Turkey Traveller explains, if someone offers you something, be it help, a cup of tea, or whatever, you might first refuse, but in the end accept the offer. Refusing a cup of tea is rude and the excuse of not having time for it is hard to accept, since it comes from someone who is there on holiday. If you finally refuse, it must be for a really good reason. And safety isn't a good reason for the foreigner: from what I know, such offers have absolutely no second thoughts behind.

2. We met Ekrem (friendly, just Eko), a 21-year old bodyguard from (Gazi)Antep, at the time we were transferring from the centre of Antalya to the bus terminal, where we would get our nightly connection to Tas;ucu. He was coming from holiday in Antalya back to his work in Mersin. He was fond of talking, in a fairly fluent English, and showed the characteristic willingness to help us poor foreigners. He showed us two photos with the Russian girlfriends he met in Antalya -- indeed, Russian girls are a fancy for the Turks.

3. During the trip to Tas;ucu I woke up during a halt in the middle of nowhere (so it seemed, so dark it was at 2 am). But we could see a sort of shelter with strings holding bananas, a few boxes with apples, honey flasks on a table, and perhaps more. Practically all passengers stepped down, immediatly reaching out to the bananas without ceremony to eat one or even two! The driver and his two assistants participated in this surreal scene, which was very confuse, to say the least, and lingered for more than 20 minutes. I watched from inside the bus, and as far as I can tell each banana-eater finally took an armful of bananas and payed.

4. The minibus we took on arrival in Cyprus, to the centre of Girne (KKTC), although it was packed full with people and luggage, stopped to pick up two young men standing by the road with a couple of handbags. After they literally climbed inside and slid somewhere to the rear, I wondered: how are they going to pay the fare? The answer came quickly: a 1 MTL note was relayed through a line of passengers to the front, till it reached the driver who, without interrupting the trip, prepared the 2 notes of 0.1 MTL as change, which were passed along the same hands back to the passenger. I had heard this system was common, now I witnessed it.

5. One of the hotels that was recommended to us in Girne was full, but before we turned our backs we saw a warning forbidding local students to attend the bar in this hotel. We kept wondering about this, but we did not dare to ask anybody.

6. In Girne I realized I had forgotten the bag I was carrying with some important stuff (guides, maps, my little Turkish word list, and also a handful of delicious pistachios I bought in Tas;ucu) in the sea bus that brought us from Turkey. I immediatly gave up the hope of recovering it, but, at the Fergün counter where we were paying the taxes the next day, as we were heading back to Turkey, one of the managers displayed that same bag, thinking it belonged to somebody else! Of course I claimed it and it was no problem to have it back to me, pistachios included. But, if you wonder, this was not supposed to happen... That bag crossed the KKTC border and surfaced at the counter of a different sealine company, and was shown off exactly at the time I could see it...

7. Sedat owns, or at least manages, the Pansyion Weisse Villa, where we stayed at Alanya. The German name indicates how much this particular city is colonized by German (and Nordic) tourists, many of whom seek diving courses announced as Tauchschule. Sedat is a Kurd, and perhaps it is thanks to him that I could taste what was, unaware, my Kurdish meal of this trip. I asked him the direction of a good restaurant in Alanya, and he indicated one, named Simge, at the center of this sleepless town, located between the bazaar and the Is; Bank. I noticed a few funny things in the long menu, first the fact that there were very few Turkish specialities, second the name of the house speciality, which was in its original designation (Denizati) in all languages except in Turkish! For Turks, the name was erased and "house speciality" hand-written instead. Though I thought this was strange, I chose this speciality, which consists of small (lamb?) meat pieces, with a distinct piquant flavour (very different from that of the Adana Kebap), served with a generous salad, and enjoyed it very much. To thank Sedat for his graciousness, I thought it would be nice to offer the copy of the Skylife magazine we took from the airplane, only with the maps stripped from it, because it was bilingual (Turkish and English) and might be useful for him to improve his mastering of the language.

8. When we arrived at the Atatürk Avenue in Alanya, where Sedat told us to wait for a minibus that leads to the Bus Terminal, we found a café where we ordered our breakfast. All dialogue (?) was in Turkish, including for trying to confirm whether the referred minibus would be coming by that café. The response was the reassuring gesture showing the palm of the hand, as if saying: «don't worry, stay put and leave it to me», in this case it meant «enjoy your breakfast and I will watch the next minibus that comes by and will make it stop». And this is what happened, with him dividing his attention between the seated costumers and the movement in the avenue.

9. At Izmir

I almost felt desperate trying to get a hotel near the harbour. Using the

hotel list on one of the pages I saved from the Skylife magazine, I called

the Kýzmet hotel (3*) by telephone and confirmed the availability

of free rooms, while for some reason they told me I was only 200 m away.

So we walked. There must have been a zero missing in that estimate, and

our patience was already over when I approached a group of 3 young people

(one man and two girls, the latter probably sisters) standing at a crossroad

to ask for the direction, showing them the hotel address. All in many gestures

and some Turkish. Since they didn't know where the street was, they asked

first some people passing by, to no avail, and then went to a telephone

cabin (I was glad I could supply the telephone card I bought at Ortaca).

After that, the same reassurance sign with the hand. The two sisters were

having fun with the situation, gazing at us and laughing all the time.

One minute after the phone call, a dazzling BMW arrived, they put our bag

in the luggage compartment, told us to sit inside and drove us, the two

girls sitting together on the right front seat, the two of us on the back

with the man who came with the car on the back, and the one who did the

call at the wheel. What a car, by the way! Well, after another minute we

were in front of the hotel. We were very near indeed, but it was big fun

for everybody this little service they did to us. A shake of the hand while

the two sisters were sitting now on the back seat, the two young men on

the front, and there they went for their week-end programme, I suppose...

9. At Izmir

I almost felt desperate trying to get a hotel near the harbour. Using the

hotel list on one of the pages I saved from the Skylife magazine, I called

the Kýzmet hotel (3*) by telephone and confirmed the availability

of free rooms, while for some reason they told me I was only 200 m away.

So we walked. There must have been a zero missing in that estimate, and

our patience was already over when I approached a group of 3 young people

(one man and two girls, the latter probably sisters) standing at a crossroad

to ask for the direction, showing them the hotel address. All in many gestures

and some Turkish. Since they didn't know where the street was, they asked

first some people passing by, to no avail, and then went to a telephone

cabin (I was glad I could supply the telephone card I bought at Ortaca).

After that, the same reassurance sign with the hand. The two sisters were

having fun with the situation, gazing at us and laughing all the time.

One minute after the phone call, a dazzling BMW arrived, they put our bag

in the luggage compartment, told us to sit inside and drove us, the two

girls sitting together on the right front seat, the two of us on the back

with the man who came with the car on the back, and the one who did the

call at the wheel. What a car, by the way! Well, after another minute we

were in front of the hotel. We were very near indeed, but it was big fun

for everybody this little service they did to us. A shake of the hand while

the two sisters were sitting now on the back seat, the two young men on

the front, and there they went for their week-end programme, I suppose...

10. I was starting to smoke my narghile (water pipe) at what I like to call the "Izmir smokers club". It was packed with quiet men playing cards, backgammon, or just watching, many of them smoking narghile in composed posture, when one of them, after knowing we were Portuguese, asked whether we could speak Italian. And we talked in Italian for nearly 2 hours about everything, from language to earthquakes to culture to soccer to politics to tourism to emmigration and even to religion. His name is Ahmet and he was just finishing his holidays before returning to Italy where he works and is married to an Italian. He kept offering us tea, and so we tried overall 4 kinds only during this evening at the "club". I think he was delighted, not least for the fact he could use his excellent mastering of Italian to communicate with foreigners. All his acquaintances nearby were watching his prolific talk in an idiom that probably they did not understand. But the most amazing was his farewell, with a handshake followed by kisses on both cheeks. I assumed this was flattering, and he did not take long to clarify: «com' un turco» (like a Turk), he said.

11. It was at dinner in the ship from Izmir to Istanbul, sitting close to what appeared to be a very well-to-do couple returning from their holiday house in Bodrum, that we had a further opportunity to discuss life in Turkey. The lady said, word by word: «people in Turkey are dying to be part of the European Union», to describe their belief on the EU membership solving all economical problems in their country. They felt a little upset by learning that our experienced views were not as favourable as they expected. Our criticism was more or less in the following lines: at least Turkey decides for itself, even if in the wrong directions sometimes, but does not have to bow to that elusive authority in Brussels.

12. By the last evening in Turkey, spent in Istanbul, we were looking for somewhere to have a snack and a cup of tea. There was a nice esplanade at the foot of the Galata Tower but we needed to buy the food somewhere else, while they served the teas at our table. The waiter recommended one of the groceries that was still open nearby. Inside that grocery was a very cheerful elderly, with a notable moustache and laughing eyes, whom I asked if he could sell me a sandwich. Instead, I understood I could buy a piece of bread and the cheese to go in it separately. He cut a piece of bread and opened it, then asked me to confirm how thick I wanted the slab of cheese to be cut. He weighed it, asked for 0.485 MTL for the bunch, then went on to prepare the sandwich for me, free of charge. All in front of a young man sitting at the corner (I bet his grandson), who was visibly amused with the situation.